5:30 AM: I just got back from dropping Paul off at the Sarasota airport, an early wake up for both of us especially since the time changed overnight to daylight savings time so we effectively lost an hour. He’s headed through Dallas on his way to Las Vegas for his second Pfizer coronavirus vaccine shot but the weather looks troubling at DFW.

We just haven’t had much luck with that airport lately. On our return flight from Palm Springs a thunderstorm diverted us to Austin which delayed our arrival by many hours. It was my second diversion at that airport — a few years prior when flying from Querétaro, Mexico storms diverted us to Houston which was a huge pain since we were an international arrival which complicated the security.

But hopefully things will be just fine for Paul today, I’m thrilled he is getting his second shot which means he will soon be free to interact more socially and travel more. Things are looking up, many experts are saying that things will begin to feel much more different in the next 45 days or so as vaccine injections continue to ramp up.

Paul says the airport in Sarasota is very busy today and it’s an early Sunday morning — this is probably due to the spring break holidays that hit in mid-March. The flights are very full so he actually used one of his 16 space-positive non-revenue travel passes to ensure he could get there for his appointment. People are quickly returning to travel — news reports today say Friday’s airport totals were the highest since COVID-19 shut everything down a year ago, and that soon flights will be back to pre-pandemic levels.

I realize people are anxious to reclaim their former lives, but all this feels a bit premature — only 10% of Americans are fully vaccinated and with no clear scientific understanding of whether vaccinated people can still transmit the virus, there could be a spike after all this new social activity. Not just in airline travel but many states are completely dropping restrictions and opening up fully.

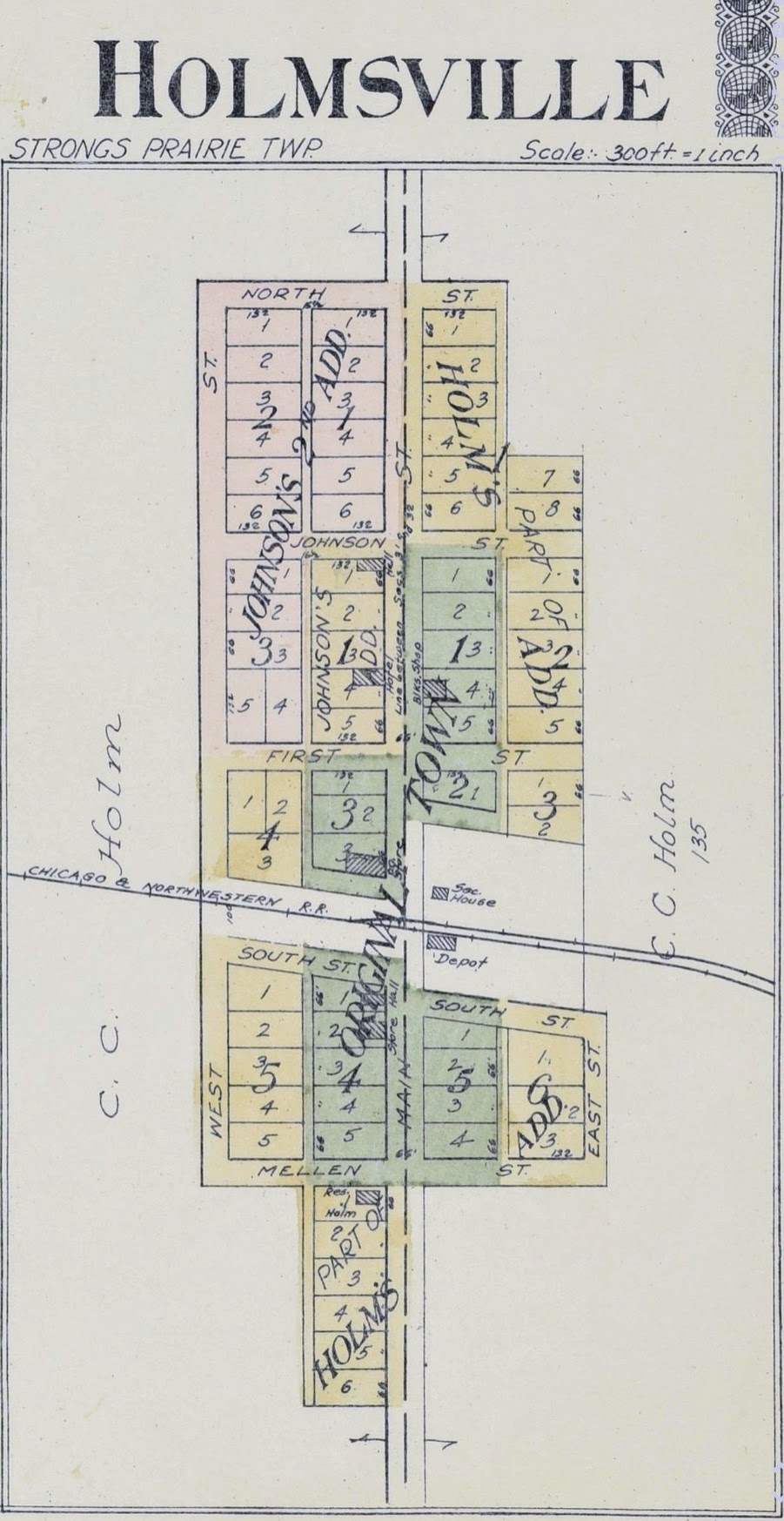

Kelly sent me and Erik a short genealogy from Aunt Inga’s son Ian Worley of the more recent family generations, the “Soley” clan (or Sorley as known before arrival in the New World) which isn’t a direct bloodline since Dad was adopted into this branch. My “real” family surname is Holm, many of whom first settled in Wisconsin before moving out to the Dakota Territory and eventually to Alberta, Canada. There was an unincorporated village near the Wisconsin River and on the Chicago & Northwestern Railroad called Holmsville but this name later changed to Dellwood after a Chicago developer built a summer community just south of the village center.

From Adams County 1919, Wisconsin (published by Geo. A. Ogle)

My father’s family came from within this township triangle that encompasses Holmsville, Strongs Prairie to the north, and Arkdale to the east. Dad’s great-grandfather Lars Olsen Holm immigrated to this area from Telemark, Norway to farm in the mid-1800’s. In Wisconsin, Lars had six children including my dad’s grandfather Oscar Holm who married Sigrid Rosgaard, who was born Numedal, Norway.

Oscar and Sigrid bore 12 children, including my grandfather Orin Hilfred Holm who emigrated from Wisconsin to Canada to homestead in Shoal Creek, near Barrhead in rural Alberta. The western provinces were rapidly being settled by farmers in the wake of the Yukon gold rush. Barrhead started as a settlement along the Klondike Trail, which was originally a First Nations trade route used by the Tlingit Indians. After gold lost its glitter, land-seekers arrived in droves during the early 19th century and this immigrant wave brought my family.

My grandfather Orin married Dena Silgard (born in Montana) who lived on a farm near Freedom, Alberta. They had four children: Sylvia, Clifford, Tommy and my dad John. Tragically, Dena died during labor with my dad. Purportedly the country doctor was drunk and administered too much ether while inducing a “twilight sleep”, which was popular at the time for a painless childbirth.

My dad grew up in Friendship, Wisconsin after his aunt Selma (Holm) Soley adopted him as an infant. Dad kept close ties to his brothers and sister throughout his life, and visited them in Canada annually in his later years.

To me the Canadians were always the “unacquainted” side of the family when I was growing up, simply because they were so geographically removed from my everyday life. I occasionally received letters from my aunts and uncles, always very loving messages and sometimes thoughtful gifts. Uncle Clifford gave me a tie clip and cufflinks for my high school graduation. Uncle Tommy gave me a pewter mug. I recall chatting with Aunt Sylvia on the telephone once. These Canadian encounters were mere flashes in my childhood mind. Dad regularly shared bits and pieces of family lore, but these never resonated centrally.

Dad and Erik visited them once in the early 1970’s, taking the train from Dubuque to Chicago then all the way to Edmonton. I was just a toddler so wasn’t able to join them but it must have been an incredible journey!

Dad always enjoyed his connection to his siblings — I think growing up was a bit lonely for him since his sister/cousin was 21 years older and his adopted mother was more of a grandmotherly age. Yet his birth family never considered him anything but a brother, it’s just the physical distance made deep bonding a challenge.

Erik and I visited once in the 1990’s with Dad and Kelly. We enjoyed a few days in the long summer solstice days, visiting with our aunt, uncles and cousins, seeing the farms, dancing in the opry, and eating the hearty country meals. I’d very much like to go back and spend more “slow” time there getting to know the land and people a bit more.

Paul and I planned a trip in the summer of 2017 to visit the Canadian Rockies and swing through Barrhead to scatter some of Dad’s ashes on the land where he was born. But our plans happened to coincide with Canada’s 150th anniversary of Confederation so all flights, hotels and cars were booked heavily — we didn’t want to fight the crowds so that important trip is still on hold.

Erik and I were texting each other yesterday on our family genealogy and how much it is a part of our identity and how little it actually matters in today’s world. Considering how fragmented families have become with ease of physical movement and new ways to connect in the information age. In many ways we dilute our biological family ties by moving apart, while we reimagine relationships through growing “intentional” families. Cultural heritage is an even far less important factor in one’s identity today.

Dad’s generation was the last to have 100% Norwegian ancestry, and the first to have English as a first language. It’s a rapid transformation — Old World family heritage is subsumed quickly. I don’t identify as Norwegian in any way but through my genealogy, unlike my dad who learned Icelandic in retirement to connect with his heritage since it’s considered a dialect of Old Norse. I simply don’t see the need.

I see this “cultural severance” phenomenon with my Indian friends — so many moved here for the technology industry in the past two decades, and now their American-born children are growing up with very different cultural needs and desires. It’s the story of America, really.

It’s probably why some Americans are unusually obsessed with “heritage”. Usually it feels safer to identify with “like” people. It’s why we have racial and cultural division in this country — fear. The shrouded (but pervasive) bigotry in eastern Iowa where I grew up is based solely on the fear of outsiders.

Specifically: Blacks, Asians and Latinos — really anyone who looks and sounds different. The despised minorities and immigrants of past generations eventually assimilate and learn to despise the new arrivals. Our xenophobia in the Age of Trump is nothing new, really. We’ve been this way since our inception.

But we’re not that different at all. Americans are not pure breeds. And genetically speaking, there really is no such thing as separate human races — human beings are 99.9% identical in their genetic makeup. Science shows that humans cannot be divided into biologically distinct subcategories. So why does cultural ancestry matter? We lose it very quickly, usually in just one or two generations.

Only Erik’s daughter Nissa and her two children continue the Holm-Rosgard-Silgard bloodline. All my cousins on that side of the family are childless. So am I. In today’s world this lineage cessation will become far more frequent, as fewer and fewer children are born (many couples I know have no children). In the modern industrialized world, long gone is the need for Oscar and Sigrid’s twelve children. Medical science, the modern economy and information age have dramatically shifted the paradigm.

The future will be less about proliferating in quantity. It will be about “quality”: eliminating disease, stabilizing desired attributes, improving usefulness. Human beings have done it for thousands of years with plants and animals. Now with genetic technology such as CRISPR we are at the dawn of a new eugenic age.

There is much to hope for, and more to fear. The homo sapien family is set for a sure — but uncertain — transformation. And our identities will mean entirely different things.