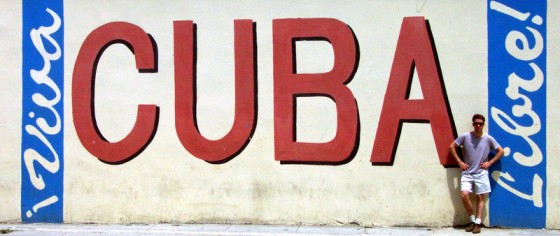

In the waning days of the Clinton administration, we threw caution to the wind and booked flights from Toronto to Havana, realizing a lifelong dream of mine to visit Cuba and taste firsthand the spicy history, politics and culture of this proud island nation. Although illegal for US citizens to spend money in Cuba without authorization, we decided to buck this restriction and Trade with the Enemy. We are Americans after all and Freedom is our established right and responsibility.

Havana is a vibrant city, a feast on the eyes and ears with music and color filling the air. The colonial core, la Habana Vieja, is an architectural gem. We stayed at the Hotel Ambos Mundos, where Hemingway wrote For Whom The Bell Tolls, and delighted in the soft boleros playing breezily on the lobby piano. On the rooftop terrace, where I enjoyed fine views of the surrounding streets and the Bay of Havana in the distance, I sipped my first mojito on tierra cubana. It was a marvelous start to a magical week. Sometimes rules are meant to broken.

We walked the many neighborhoods of Havana:

- Old Havana where we stayed, showcasing the main colonial buildings, crumbling facades and colorful miscellanea hanging out of windows: drying laundry, flags and ¡Viva Fidel! banners, flowers and plants of all sorts, and elderly locals poking their heads out to watch the world pass by on the streets below.

- The Malecón, where the city faces the water, with waves splashing into the streets and wetting passersby. Habaneros of all ages come here to enjoy the fresh sea breezes, fish and play in the craggy tide pools.

- The Vedado with its prerevolutionary upper-middle class homes and now an amiable residential district featuring John Lennon Park and the US Special Interests Section, in front of which Cuba confronts its enemy directly with the bold Plaza Anti-Imperialista.

- Plaza de la Revolución, monumental square celebrating the Cuban Revolution with images of Che Guevara, José Martí, and other Cuban revolutionaries from all epochs.

- The Prado, replete with chatty cafes and hordes of locals in spandex on paseo. A people-watching extravaganza.

- The hilltop defenses above the Havana harbor entrance: the iconic Castillo del Morro and the Fortaleza de La Cabaña, with a splendid colonial-era changing of the guards ceremony.

Accessible and interesting in every way, Havana rewarded our exploration of this fascinating city. We drank daiquirís beneath the tropical moon at the Hotel Inglaterra terrace and gazed down to the vintage cars passing in the wide, empty boulevards below. In the streets, we listened to sweet son montuno rhythms, watching locals dance and sing along.

We learned of modern Cuban revolutionary history at the intriguing Museo de la Revolución. Housed in the former Presidential Palace, we contemplated the gold-plated telephone and other extravagances of the Batista regime, and read about the wide economic and racial disparities in Cuban society before the revolution. And we evidenced the strong Soviet ties to the island during the Cold War: tanks, guns, technology, even a USSR mission suit worn by the first Cuban (and Black) person in outer space. It was an engaging visit with a markedly “Revolutionary” slant.

On the second night we treated ourselves to the touristy (but must-see) Tropicana Club cabaret. Upon being seated at our table, a full bottle of Havana Club aged rum appeared. Within moments dozens of Cuban dancers in resplendent carnaval regalia masterfully dazzled us for over two hours. The accompanying orchestra provided great music which spanned the sounds and styles of Cuban music through the ages: rumba, son, guaguancó, danzón, nueva trova, timba… it was pure delight!

The following evening we strolled through the city streets watching block after block of kids playing baseball with broomsticks and bottle caps. We had brought school supplies to give to a local school (which was appreciated) but in retrospect if I had stuffed my bags with baseballs to distribute around town, I would have been regarded as a real hero. Baseballs were in sore demand in this island where béisbol reigns as the national sport.

We arrived at the Coppelia ice cream parlor near the university, a popular gathering place for locals on paseo who enjoy the tasty treat in the cooler hours of dusk. Nearby, at the Cine Yara film center where the locals gays hang out, we saw many young friends (cautiously) enjoying a night out. In the early years of the Revolution, gays were sent to forced-labor camps for “rehabilitation” — this memory is still alive in the Cuban gay community although tolerance by the general public has risen steadily since the 1990’s.

We went for a nightcap at the restored Hotel Nacional, emblem of the Mafia-run and casino-driven tourism of the pre-Castro days. Despite its monumental scale, we were not impressed and preferred the smaller boutique hotels in the Habana Vieja zone. It is a strong and sad reminder of the two-tiered system alive in Cuba today: local vs tourist, peso vs dollar. At the time the US Dollar was the de facto currency for foreign visitors: for example, at 20 Cuban pesos to 1 USD, the camello bus cost $1 — Cubans paid 1 peso (or $0.05 USD) while tourists paid $1 USD). While still a deal for tourists, routine monetary transactions separated us from them.

There were dollar stores which were jammed with imported goods for the few Cubans who had access to hard currency, either sent as remittances from family in the US or earned in the recently (but ever-so-slightly) liberalized economy.

We tourists spent our days largely free and unfettered while Cubans were regularly stopped and questioned by police, often after speaking with us. Tourists never saw a line while the locals seemed to queue endlessly at government agencies, state ration stores and transportation hubs. We visitors had our own special tourist police to protect our comfort and convenience, while the locals faced civilian spies (the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution, or CDR for short) to protect the State from them. Everyday Cubans went without, subsisting on meager rations and limited to what the astonishingly low state wages could provide. For tourists, luxury items could be produced in a flash once dollars appeared: fine meals in private homes with lobsters, chocolates and rum-on-the-rocks, rare cigars, las jineteras or female sex workers.

Two standards, two currencies, two worlds dividing the island. Those few with access to dollars (and other hard currencies) have broad freedoms; those multitudes without live with considerably more restrictions. Hardly what the la Revolución promised, but without the friendly economic support of the Soviet Union and challenges resulting from the US trade embargo, the socialist island nation still faces the reality of a two-tiered society defined by dollars.

Yet there were many things that impressed me about Cuba: the strong sense of cultural and national pride among pretty much everyone I met; the racial and gender equality visibly present; the advanced medical and educational opportunities afforded to all Cubans and extended through energetic diplomacy to other developing nations; the advances in agriculture and green energies; and the relative poverty of Cubans which doesn’t compare to the pathetic and complete destitution I encountered parts of the Andes, Brazil and Central America. Cubans may be poor, but they are healthy, educated and generally nourished.

While poor, Cubans are well-educated, resourceful and dignified. They seem to only lack opportunities that the yet-to-be-diversified island economy can offer. This was especially true of younger Cubans; while the older people I encountered (who presumably remember the severely segregated pre-Revolutionary days) defended Castro and his accomplishments. But for the younger Cubans I encountered, the hollow echoes of the Revolution’s past provided little consolation to the present difficulties. Understandably, I sensed they yearned for more: more money, more opportunity, more freedom, more world.

We found Havana an especially safe and friendly city, very easy to navigate. Many Cubans greeted us, eager to ask about our impressions of Cuba and life in the United States, and they spoke freely about the hardships of daily life in Cuba. A police state, official ears are usually within close distance, so the locals were careful to not denigrate the Cuban government. Interesting, they never refer to Fidel Castro by name but rather by gesture — they stroke their chin to imply the “Bearded One”.

Many Cubans I encountered knew of friends and family living in the United States and expressed genuine warmth to my compatriots. One local told me “We Cubans have nothing against the American people; it’s the two governments that don’t get along”. One middle-aged lady told me her sister fled to Miami in recent years and is now a millionaire with a mansion, or at least according to the extravagant descriptions in letters. I explained that in the United States life is not exactly a bed of roses for new immigrants, they often toil long hours at menial jobs for low wages, but I don’t think she believed me.

I’ve encountered this attitude all over Latin America, starting with Uruguay (then under military dictatorship) in the 1980’s where the popular image of the US was projected through the lens of glitzy Dallas and fairytale Hollywood films: the land of plenty where everyone is beautiful, life is glamorous, homes are monstrously large, no one works, and money flows like water. This misconception is magnified in areas of economic or social stress, the separation of the Cuban people is palpable as la Revolución limps along its increasingly solitary socialist path. There is a cultural richness and striking identity in the Cuban people that is perhaps unparalleled elsewhere in the hemisphere, but it is also a nation growing increasingly more “island bound” as global capitalism marches forward without it, thanks largely to the crippling and cruel US embargo.

The US trade embargo is a sham. It hasn’t accomplished its purported goals in decades, yet we continue to enforce the policy despite nearly universal world condemnation. It clearly harms the Cuban people, while providing the Revolutionary regime the perfect imperialista foil, which it adroitly uses to justify the human rights restrictions and abuses. Most experts agree that the Cuban government would collapse under the weight of a steady onslaught of visiting Americans and their trailing tourist dollars. As quickly as the Eastern Bloc nations did once the walls came down. While Cuba welcomes many tourists from modern democracies (Canada, United Kingdom, Continental Europe), lifting restrictions for the 300 million United States citizens only 90 miles away seeking sun and fun would be a game changer.

Which, of course, is a conundrum to me. I celebrate many of the accomplishments of revolutionary Cuba (but reject the human rights shortcomings). To simply do away with the Castro’s socialism and impose a capitalist system would unravel the careful social, cultural, educational and medical advances the island has worked so hard to provide to all Cubans. The Miami Mafia is waiting in the wings, ready to restore the oligarchy lost a half century ago. Change will come to Cuba, and I sincerely hope (and trust) the pueblo cubano can preserve the best of its special society while providing democracy and economic opportunities for the next generations.

After four days in bustling Havana we bussed to decidedly quieter Trinidad, a colonial town on the island’s south shore. For centuries separated from the rest of Cuba by the forbidding Sierra de Escambray, the town thrived on molasses trade from the neighboring Valle de los Ingenios, the Valley of the Sugar Mills. This town welcomed the wealth of Caribbean pirates looking to invest in sugar contraband. As a result, Trinidad remains an agreeable town of singular colonial beauty, which is thankfully protected (and provided restoration funds) as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

We stayed in a casa particular, or private guest house, one of the few individual commercial ventures recently permitted to Cubans. Our host was a local art historian with a rambling colonial home, with high ceilings and lush interior patio full of tropical plants, flowers and birds. Next to our room was the workshop of his octogenarian father who tinkered day and night on electronics of all kinds: small motors, radios, automobile components, kitchen appliances.

In the evening we visited the open-air Casa de la Trova, the musical cultural center, where we enjoyed fine drinks and live music. It was a healthy mix of locals and a few intrepid tourists (not many go to Trinidad, compared to the hordes who pack the Varadero beaches on the north coast) and solid Trinidad musical talent strumming, crooning and swaying in the tropical evening breeze.

The next day we walked a couple miles to a crumbling, concrete Soviet-era hotel on a deserted beach. We rented a Hobie Cat and sailed in the warm, turquoise Caribbean for a couple hours. We lunched at the dilapidated hotel pool. Biting into his sandwich, Paul was shocked to finding a tooth: “I hope to God that is my tooth!” (it was: a cavity filling broke which unleashed the mystery fang). We had a good laugh, thankfully the break was not severe nor painful. We enjoyed the rest of the afternoon lounging on the empty beach.

Our final adventure in Trinidad was into the Sierra on horseback, led by a subdued but highly educated veterinarian. It was awesome. We rode through banana, coffee and sugar cane plantations, watching local farmers work the fields by and and primitive oxen-driven implements. We climbed into the hills and eventually arrived at a shady, pristine waterfall. Our guide left us alone for a while as we swam naked and relaxed in the refreshingly cool mountain waters.

The next day we returned to la Ciudad de Habana for a final night in the sensational city. Too soon we were airborne and Canada-bound, the enchanting island of Cuba fading slowly in the distance. A dream realized, my visit to Cuba surpassed all expectations and left me wanting far more: the Santiago birthplace of son montuno, Viñales park in Pinar del Rio, colonial Camagüey and beachy, beguiling Baracoa. I will continue to dream, especially when it comes to Cuba.*

* Dear US Department of Treasury Readers: this trip was but a dream, not in fact a real visit to the island. In the words of Calderón de la Barca: ¿Qué es la vida? Una ilusión, una sombra, una ficción… toda la vida es sueño, y los sueños, sueños son.