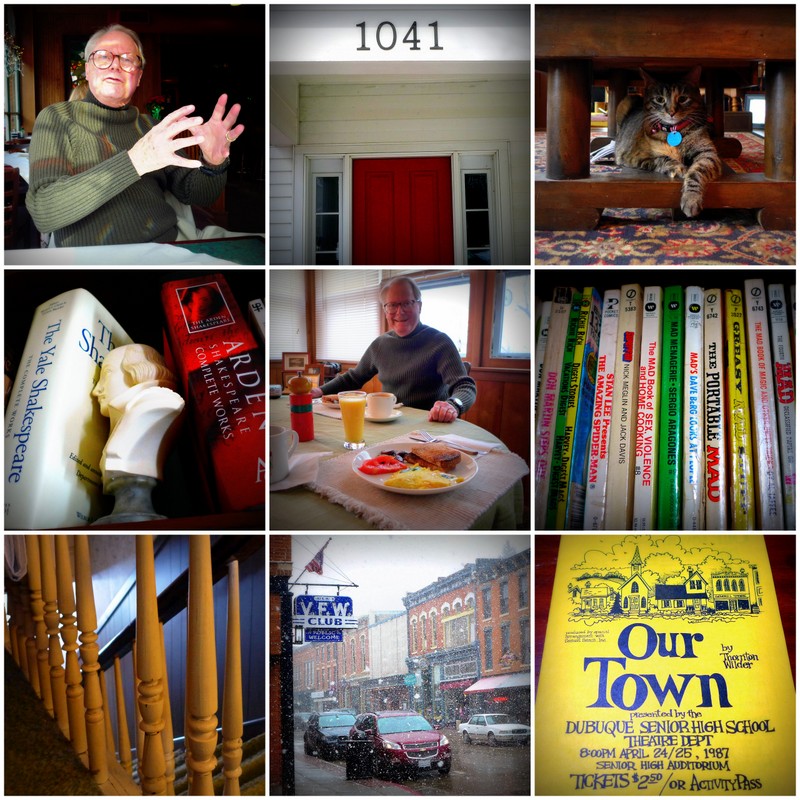

It was a gratifying return to the United States: a few days of affection and rest in my childhood home of Dubuque, Iowa. Dad and Kelly greeted me in blustery Rockford, Illinois and we drove the beautiful stretch through Terrapin Ridge to the icy Mississippi River Valley, my old stomping grounds.

After six months rambling in South America it felt good to be back with family. It was easy to adapt to non-Latino life — I found respite in simple things like hot showers, speaking English, brushing my teeth with tap water, and slumbering deeply under heavy blankets and winter’s darkness and silence.

I was treated like royalty: Dad carefully planned each meal of home-cooked fare and kept up lively topics of conversation about politics, history, academia, my travels and the wider world. We kicked back with bottles of Leinies, discussed articles from the New York Times and The Nation, and laughed in a tavern drinking pints while the snow flurried wildly outside.

Each night I fell asleep with freight trains sounding in the distance. I awoke to Dad waiting for me with a smile and a cup of coffee. I was warm and content and cared for.

While I’ve lived more than half my life away from Dubuque, it’s probably where I’m most rooted and will always find homey comfort. It is safe and familiar, where things are measured and known, my reactions predictable and my memories stored away securely.

I spent an afternoon cleaning up old papers, sorting through the blurred places and faces from elementary school, junior high, high school. Wistful feelings surface: compunction, gladness, ambiguity.

I guess that’s the key to going home: delighting in the nostalgia while accepting the ambivalence.

My childhood’s home I see again,

And sadden with the view;

And still, as memory crowds my brain,

There’s pleasure in it too.— Abraham Lincoln